Turf, Redux 1

Revisiting old ideas with new tech

#programming #gamedevelopment #ai

In which we breathe new life into old ideas, with some friendly help.

In which we breathe new life into old ideas, with some friendly help.

When underemployment provides new challenges.

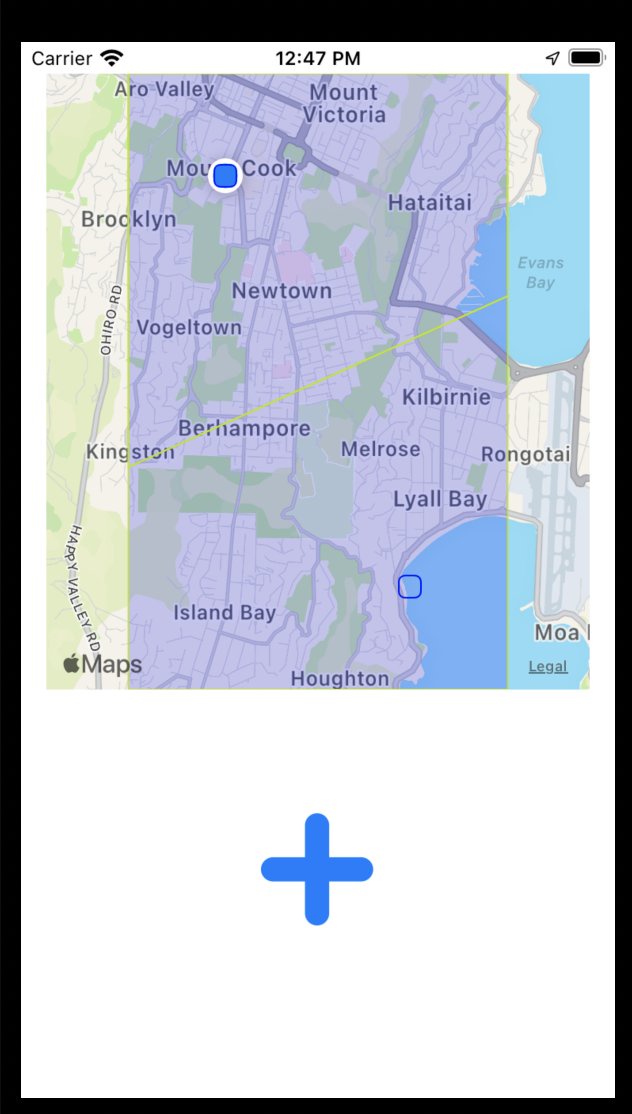

One of the first points of interest that came up when designing Turf! was how, as a mobile game that requires movement in physical space, it would be designed so that most people would be able to use it.

Again, the premise is that real people run around real space, and using the game, place virtual markers at real locations which create virtual territory, overlaid on real space.

The highest aggregated rate of territory wins.

It was immediately obvious that people who are fast on their feet would have an advantage. And also that people who are not mobile would not be able to participate in the game at all.

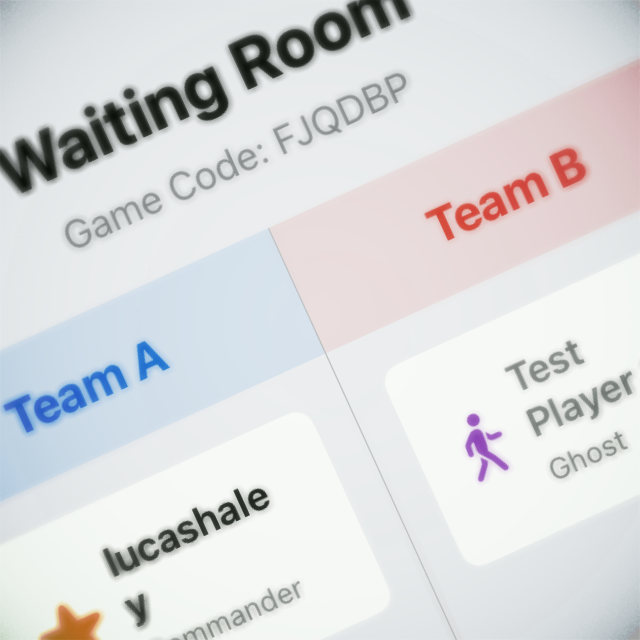

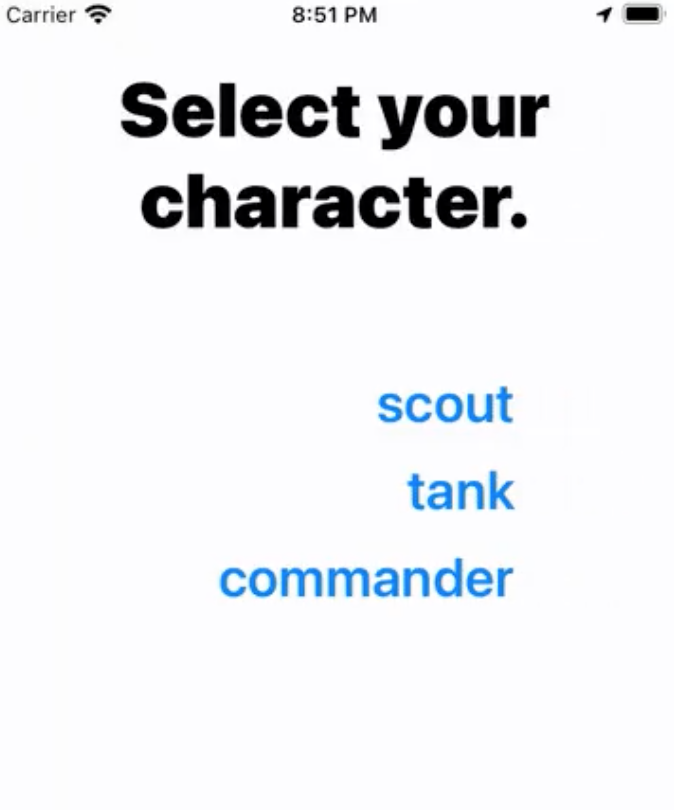

There is clearly nothing I could do about the relative speeds of players. Runners gonna run. But here is where I could lean on the RTS genre conventions to help out — player “classes”. When joining a game, each player selects a class, that provides certain abilities and restrictions. For the first pass, I included:

Scout. This class has the most markers to place, and can place them without a long delay. But each marker doesn't last very long.

Tank. With the fewest markers to place, and the longest placement time, this class shines as those markers last the longest.

Commander. Fewer markers, and quite a long placement time. But the Commander also has the extra ability to see the opposing team players' locations at all times — other classes can only see opposing team players' locations when they are in friendly territory.

Hopefully you can see how these classes and extra abilities help soften the imbalance from physical advantages. Further classes will include:

Ghost. The mirror to the Commander — remains invisible at all times.

Leech. Few markers of their own to place, but can “drain” enemy markers and take them over.

Drone. Not sure what to call this one, but this class would effectively allow a player to participate without physically moving. Instead, they would send a virtual “drone” to specific locations to place markers. But if that drone gets caught in enemy territory, it's lost. I think the intention behind this class is to allow participation from players who may not be as mobile as others, and can virtually participate.

It was also important to me to use system UI as much as possible. That way I could get the most built-in support for voice commands and other accessibility features. Visually, I'm trying to keep the UI clean, with high contrast, and large, easily readable text. Because for this game, I can. So that's good.

So I’ve been working on a mobile location-based game for about ¾ of a year now, and thought I should share more details.

When starting out on the project, I wanted to try creating multiplayer functionality. Mainly because it's really fun playing with friends, but also because it's a tough nut to crack. But I also didn't want to jump into the deep end of 60fps/physics/vfx network transport — after checking out the Unity and Unreal solutions (both built-in and third party), it just seemed like too much to tackle with the limited time I had.

But I love turn-based multiplayer games (see: Pocket Tanks, I love that stuff), and it seemed like an easier place to start.

Next, I wanted to do something with mobile devices — specifically, something physical. I wanted to see if I could make a game that requires movement.

So the gameplay I ended on is this:

Players run around the real world, and use their devices to place virtual markers that create virtual territory. The team with the most owned territory at the end of the time limit wins.

This comes with some interesting challenges:

With all of those expectations, I researched a lot on potential frameworks to use. Cross-platform is the ultimate goal, but not the primary restriction. Although I’m very familiar with Unity, I wanted something that didn’t explicitly tie to that ecosystem — it felt unwieldy, unnecessary, and just heavy. I didn’t need all of that.

So I tried a bunch of mobile frameworks.

Slowly RubyMotion proved its mettle, allowing me to bring in CocoaPods for the external stuff, and visual UI with XCode (XCode isn’t even needed, which is a huge bonus — but it’s nice to use just for the UI).

After setting up the initial UI scaffold, my main goal was to get locations, markers, and voronoi working.

I had to create the Vonoroi code in Ruby, as none of the available libraries ticked every box. But that’s okay, I understand more about the sweep line algorithm now. Getting it all together was very satisfying.

Next came the real-time database. Connecting was easy — the long process was figuring out the best way to treat the data, and how to replicate it to clients. Again, I wasn’t used to NoSQL, so the idea of just duplicating data all over the place made my skin scrawl (I like normalization, okay?), but eventually I got a good schema. Client replication was hard too, mainly because Firebase docs doesn’t do a good job explaining when and why replication happens — so I’m probably totally over-forcing updates. But the data is tiny, so I’m not worried about it.

The hidden bugbear — the thing I really wasn’t expecting — was how hard matchmaking would be. It’s probably worth an entirely different post, but ultimately I wanted matchmaking to happen behind the scenes, based upon location. There were a lot of edge cases and other interesting factors. And I had to make bots, because I can’t just get humans at all hours.

In short, matchmaking was a total beast.

But I got some successful playtests, with timers, scores, and ultimately other real humans.

Right now the project is a bit stalled, as in the move to the US my priorities are elsewhere. But I also no longer have a Mac to work on. Anyone have a spare MacBook Pro they want to donate?

I haven’t been posting much about this project, but sometimes something works and you just have to show out-of-context victories. Real-time dynamic location-based matchmaking is hard.

I'm a big fan of Unity. I've been using it since version 2. I've seen it go from small upstart, Mac-only, working with other small Mac apps like Cheetah3d, to a behemoth owning a huge chunk of the game dev base, and more. I still use it every day, and teach it in my courses.

Over the last couple of years, however, I can't help but find the name of the company to be just, well… ironic. They're shooting in all sorts of directions, trying to be everything to everyone. More power to them, I guess — except that the different tentacles of the company don't seem to be talking to each other very well. The new packages don't work well with each other. There's no unity of interface, or programmatic approach. It's really sad to me. And makes teaching it so much more difficult.

Anyways, I've been trying to pull apart the new Unity Input System. It's a catch-all system for collecting user input, from console controllers to touchscreen devices. As such, it's really abstracted out. Dredging through the demo samples, the code is inconsistent and leverages some pretty obtuse C# techniques, which of course makes it that much more difficult to grok and teach. Anyways. THE FUTURE

PointerManager collects raw input.

GestureController determines swipes and taps. It assigns its own OnPressed to PointerManager's Pressed method.

SwipingController parses gestures for functionality. It assigns its own OnSwiped to GestureController's Swiped method.

Sometimes I find myself beating my head against a particular programming problem, trying to force the code, and inevitably it means I'm not thinking in the right way about it. It's like the Blaise Pascal quote:

I have made this longer than usual because I have not had time to make it shorter.

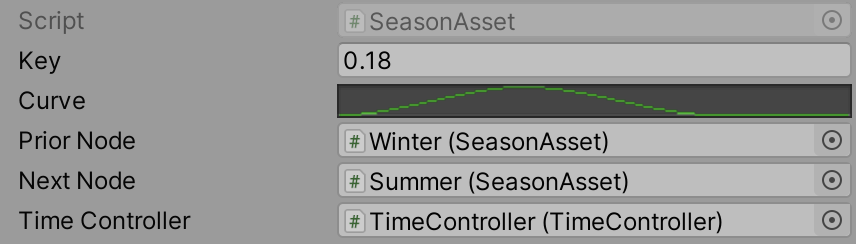

In this most recent incident, I've been trying to code seasonal cycles into a game, in which the various variables could be manipulated per-object, per-season, with custom seasons per-object. Don't ask. Anyways — here I was, beating my head against modulos and switch cases for a day and a half. Then, on a rare run, I got far enough away from the computer to remember that Unity has AnimationCurves, which basically tick all the boxes could want. It took about 14 lines of code to get to work.

It's just a nice reminder that sometimes the best coding is done with your brain, not your fingers, away from the computer.

In setting out on this project, I wanted to meet a couple of secondary goals: to actually complete a web app, and to have an overarching strategy and result for the project. I needed to make sure I could see the end result from the start, and that meant being very deliberate and measured about how to make it.

For the site I chose to use Ruby on Rails. It's a Ruby-based framework that was quite popular in the late 2000s and early 2010s, but maybe lost some popularity over the last few years. I love it — it's an elegant framework, and I appreciate the level of thought that goes into it. The convention-over-configuration mentality suits me.

A web app is great and all, but these days that web app needs support from social media. That meant setting them all up.

I host a bunch of sites using Dreamhost.com, including this blog. It's pretty good, but sometimes hosting Ruby on Rails sites can get awkward and difficult. So for this site I decided to give Heroku.com a go. Heroku is a cloud-based, platform as a service (PaaS) for building, running, and managing apps. It's got really solid support for RoR, but comes with some functional overhead — namely, using Postgres databases, and tight Git integration. I've used Git before (it's not my favourite version control), but never Postgres. So it was a learning curve for sure.

Oof. I just jumped into the design of the app as I built it. It went through many, many changes as I did. Which I think is a good thing — even though it might not have been the fastest method, I effectively had several rounds of user testing just through development.

Naturally I wanted the process of sharing these statements to be as easy as possible. One click. But it was not to be — certainly not with the moving target that is social media API compliance. Image sizes change, API calls change, oof. And what I assumed would be simple functionality — rendering out text to a fixed-size image — proved anything but. Many lessons learned there. But it works — at least, enough for a first version. More planned.

Part of the idea of this site is to ask people to take responsibility for opinions on social media. The current state of sharing allows for individuals to share a post from someone else, yet disavow agreement if confronted, to say “oh, I'm just reposting”. But the sharable image generated by We Agree That… explicitly states “I agree” — and that positioning with the first person makes it difficult to repost without taking responsibility. I've been tracking analytics, and there has been some traffic, but I hope that this gets picked up organically. If not, phase II means a more deliberate approach to publicising the site.

As Programme Lead at Massey University, I got to a lot of meetings. A lot. And, being honest, it's possible that not all of those meetings need my full attention. So I've taken to getting some concurrent work done.

The main project I've been working on is the website experiment We Agree That. The idea behind the website is that it is a place for positive axiomatic opinion — that is, dense statements that can be essentially agreed with. Much like the Euclidian axioms from mathematics, but for opinions.

A key element to the website is being able to create variants, or evolutions, of those statements. So if you are unable to completely agree with a statement, you can submit your variant that you do agree with.

It's for that reason that users are not permitted to disagree with any given statement. Instead, they are encouraged to create a variant they do agree with.

A big inspiration for this project is the Declaration of Independence. It too sets out a series of axiomatic statements as the basis for a social contract and government: “We hold these truths to be self-evident.”

Please check out the website, and feel free to add your own statements. It's still in early development, but I'd love to get some user test feedback. Part II of this post will focus on some of the technical issues in development.

Related to the prior post, I've also just got my grubby hands on the Big Nerd Ranch iOS Programming Guide. I can't wait to see how Hillegass and Conway convey the info. As an instructor myself, I've always had great respect for their ways. I still have their first Cocoa book. Ahhh, good times.