The 3 – 9 Storyboard Technique

A quick storyboard method for short films and animations.

#Animation #Instruction

As a teacher, I’m frequently working with students to refine their story ideas for short films and animations. I’ve found there are two consistent characteristics of students at this stage:

- They have not watched enough short films to understand the format

- Their story ideas are feature films or miniseries

Usually for problem 1 I send them off with a list of films to watch. For problem 2, however, it takes a little more work – dreams of extended character arcs and major set pieces are hard to let go.

One technique I have used recently is to have the students work their story from the inside out. They are used to thinking of their stories as linear, start to finish. Their storyboarding often reflects this – the first few pages (pages!) are detailed and careful, but quickly peter out. The story loses focus, the scene construction gets weaker, the film just trails off into nothing. By working on the boards as a coherent whole, the students begin to understand their story as a whole.

The technique is simple and flexible: board out your story in three (3) panels. That’s it. That’s all you get. Go.

Okay, there’s a little more than that.

I use 3x3 templates from the awesome Storyboarder, printing them out in batches.

Then the students follow these steps:

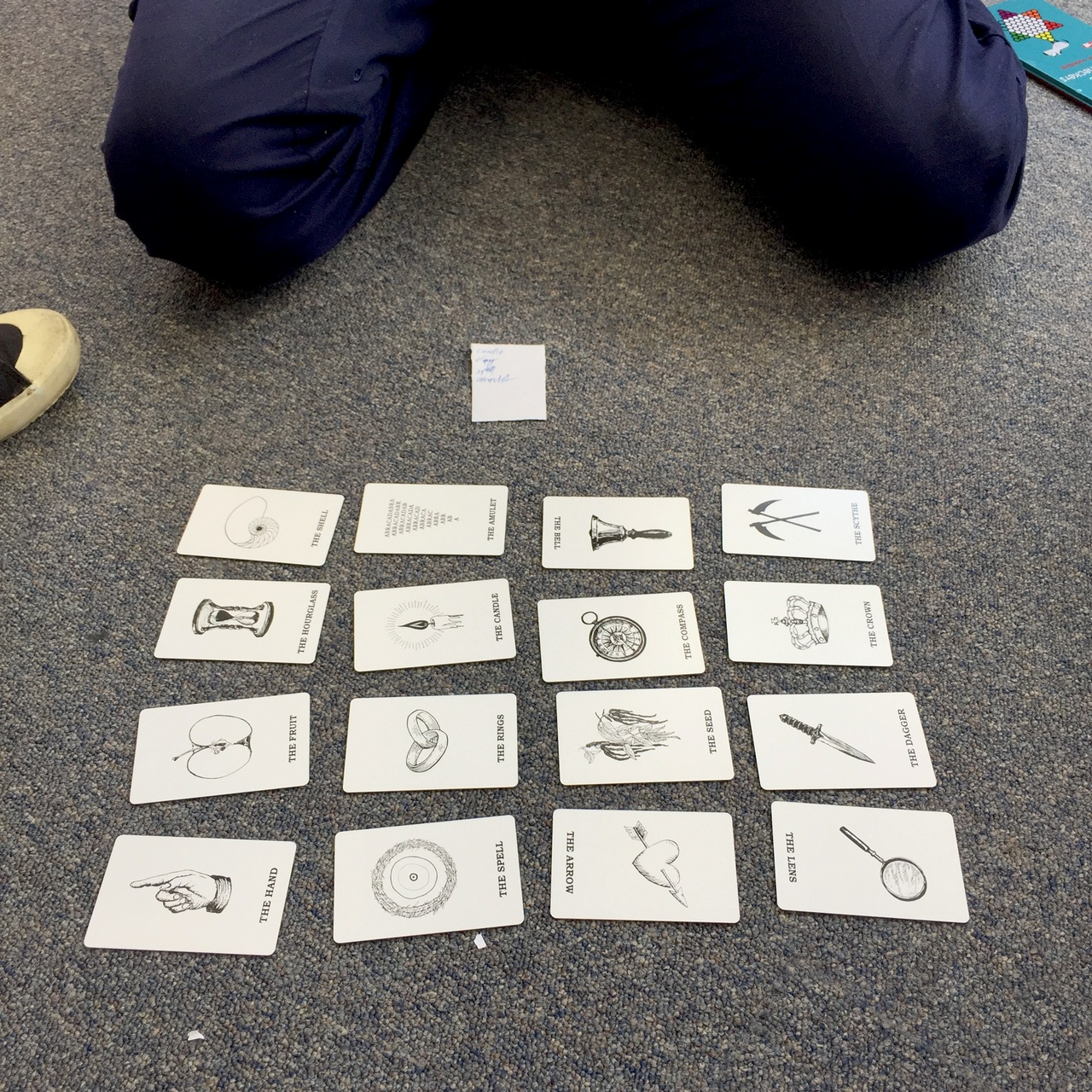

- On the first page, they board their story in 3 panels, in 3 different ways. Each row has to be significantly different – students can play with time (i.e. which part of the story to include) and space (i.e. framing). Sometimes I get them to do more than one set of three, especially if their story is vague.

This process really forces the students to think about only the main, core beats to the story. When you’re trying to say something in <2 minutes, this is critical. If they can’t, they should save the story for when they’re directors at Pixar and find a new one to tell now.

- Students then review their 3-panel stories, and help each other to assess the strengths of each.

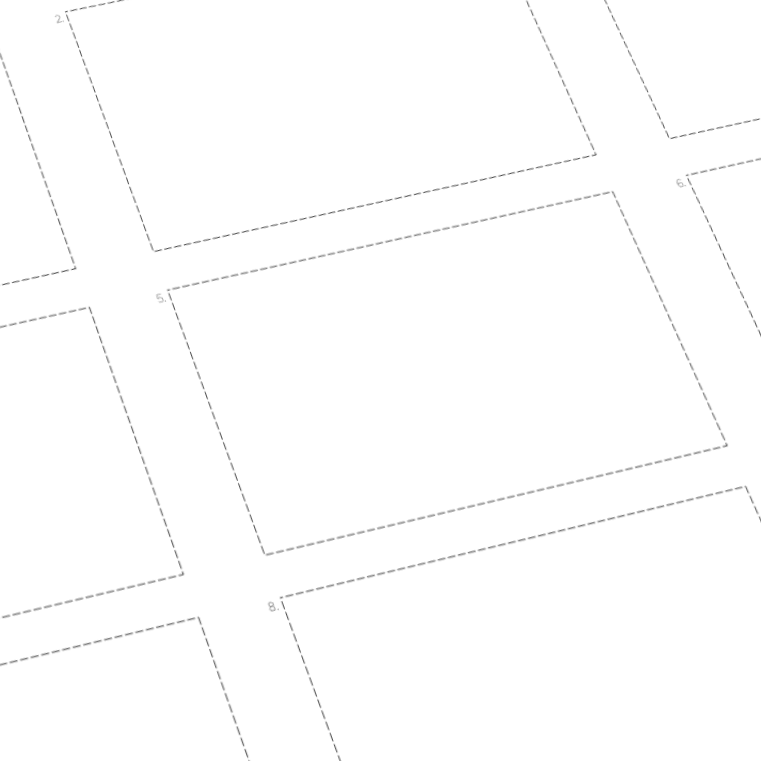

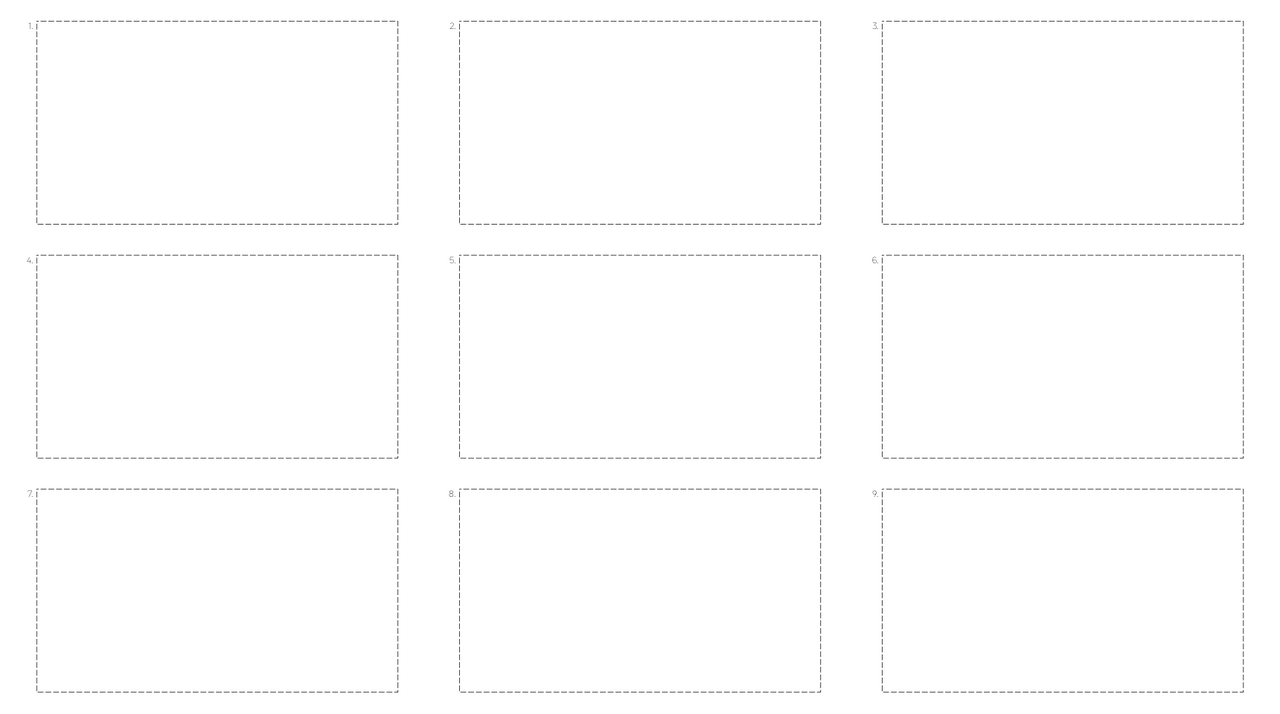

- Selecting one of the 3-panel boards, the students then take new 9-panel templates and transfer their 3 original panels into the new templates.

How they place those original panels will significantly change the pace of the film. I usually go with two initial patterns:

But there’s no reason you can’t challenge them to re-think their story, like so:

But there’s no reason you can’t challenge them to re-think their story, like so:

- They then draw the extra panels around the original ones, filling out the story.

- This process could be extended to larger arrays of boards, but I’ve found this is usually enough to get the students thinking about their story and the limitations of the format.

If you’d like to try it, you can use the wonderful Storyboarder software or print out this PDF: