Making Top Trumps with the kiddos.

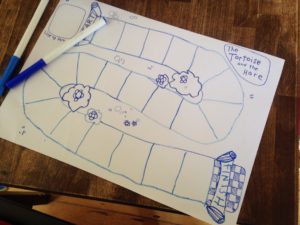

This whole 2016 election cycle was craziness. But one thing that kept popping up in my mind was the classic kid's card game Top Trumps. It's a game I have distinct memories of playing as a kid in the UK.

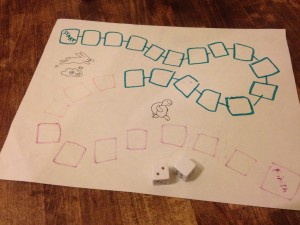

Gameplay is pretty simple: each card represents a thing (car, superhero, etc), that have a selection of numerical attributes (speed 32, handling 14, torque 22, etc). Each player's cards are stacked so only one can be seen. On their turn, a player picks one of those attributes, and the player who's top card has the highest value in that attribute collects the trick. The player with all the cards at the end wins. It's a great game for young kids, as it has some math, some social interaction, and up until the end is pretty balanced. It also has the cards in a stack instead of a fan, so young hands can manage.

The thing that interests me about the design of this game is the selection of attributes, as these attributes intrinsically carry value. Then each character embodies these values based upon their numbers, so the characters themselves carry value. So there are two points of value judgement: in describing a character, and in associating with a given character. This leads to the “top trump” card — the most powerful card in the deck. So, for example, a version that chooses for its gameplay attributes “power, speed, looks, volume” carries a different set of values than a game that chooses “heart, empathy, diplomacy, cooperation.” Secondly, a card that scores highly in those attributes will carry more gameplay weight, and therefore carry more value.

Especially for a kids' game, this feeds into a child's collection instinct and reinforces those external values. Naturally, there will be players who do not associate the numerical values with judgement values, and play the game in the abstract; but I feel that they are in the minority amongst children.

The gameplay lends itself very well to theme skinning, as can be seen from the multitude of versions out there. Currently there are a lot of versions targeting boys — Transformers, superheroes, etc. — which isn't surprising. But there were also some targeting girls — My Little Pony, Barbie, etc. Being personally invested in games for girls, I checked some of them out. Naturally the Barbie one was fairly insipid (“Which is the most glamorous? Never enough pink! Born 2 be fabulous! If it comes in sequins I want it!”). The My Little Pony one was alright (gameplay attributes: “size, magic, friendship, mischief, beauty”).

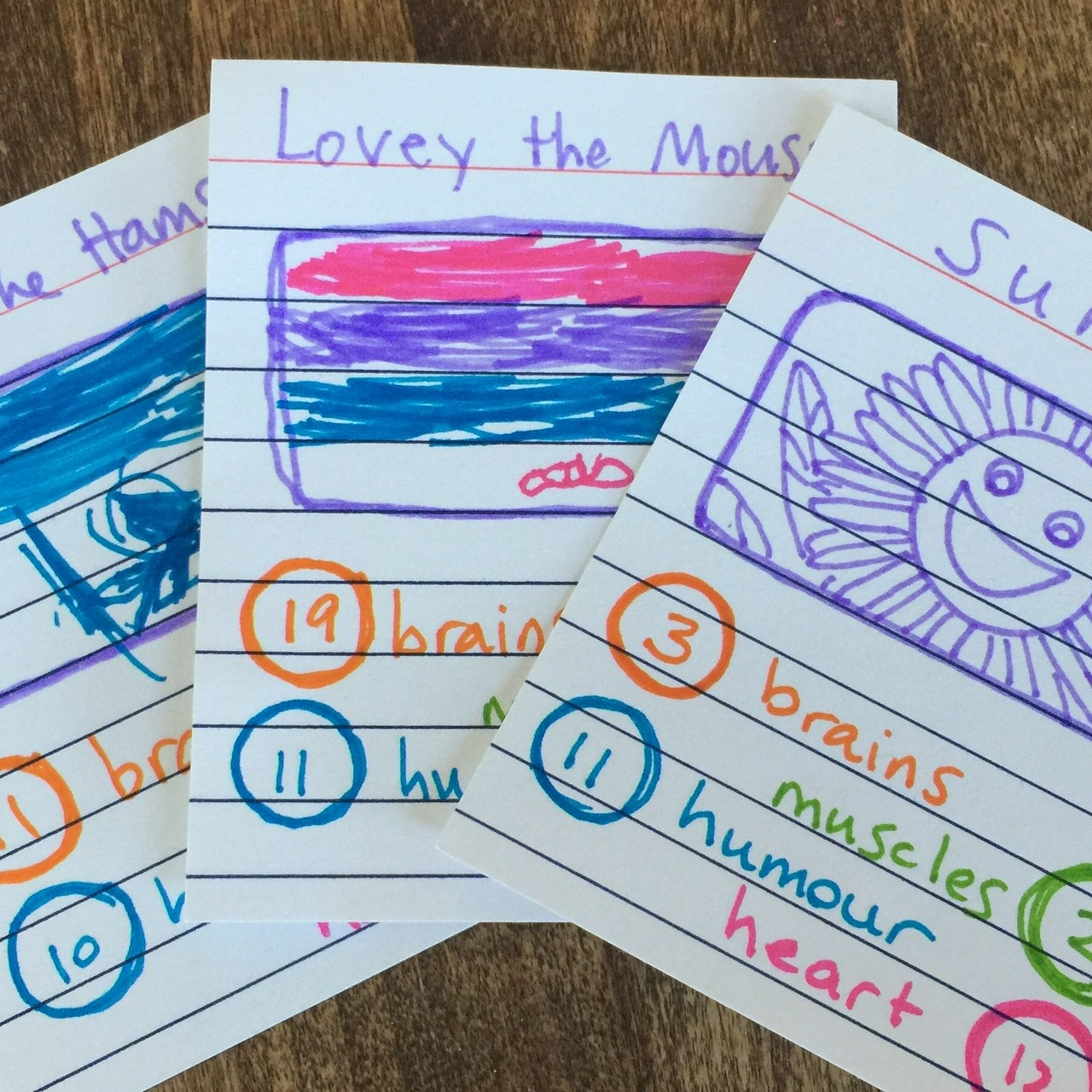

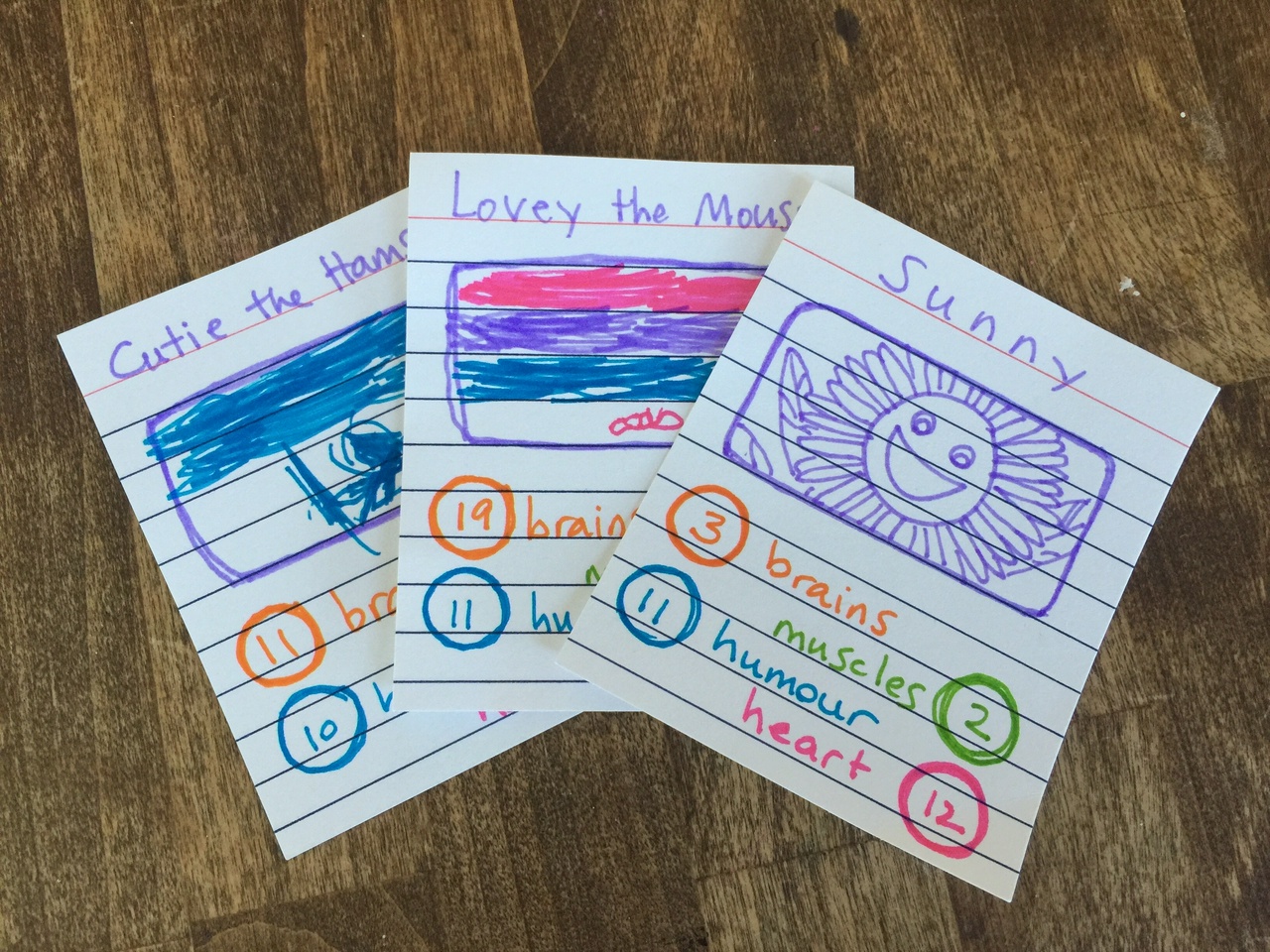

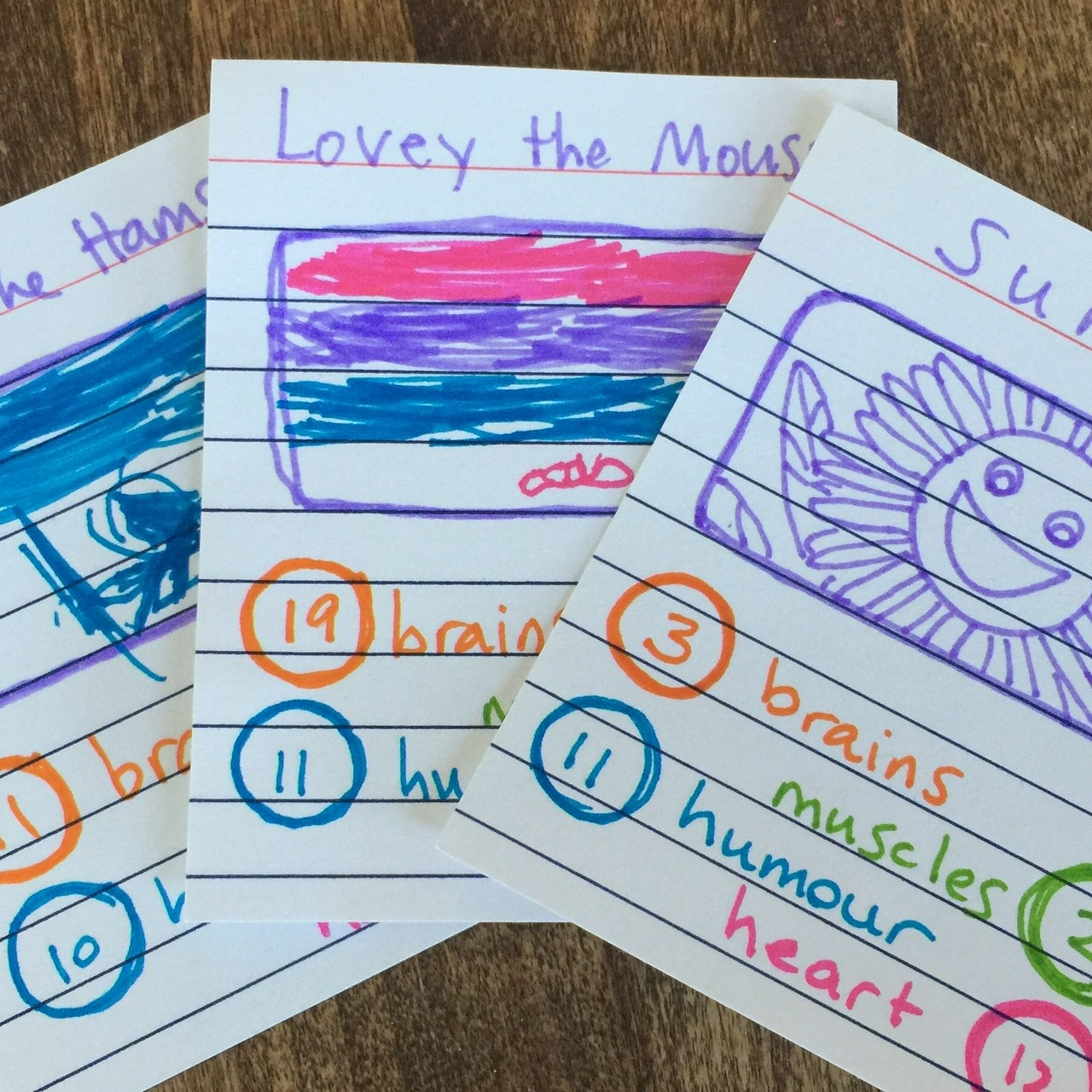

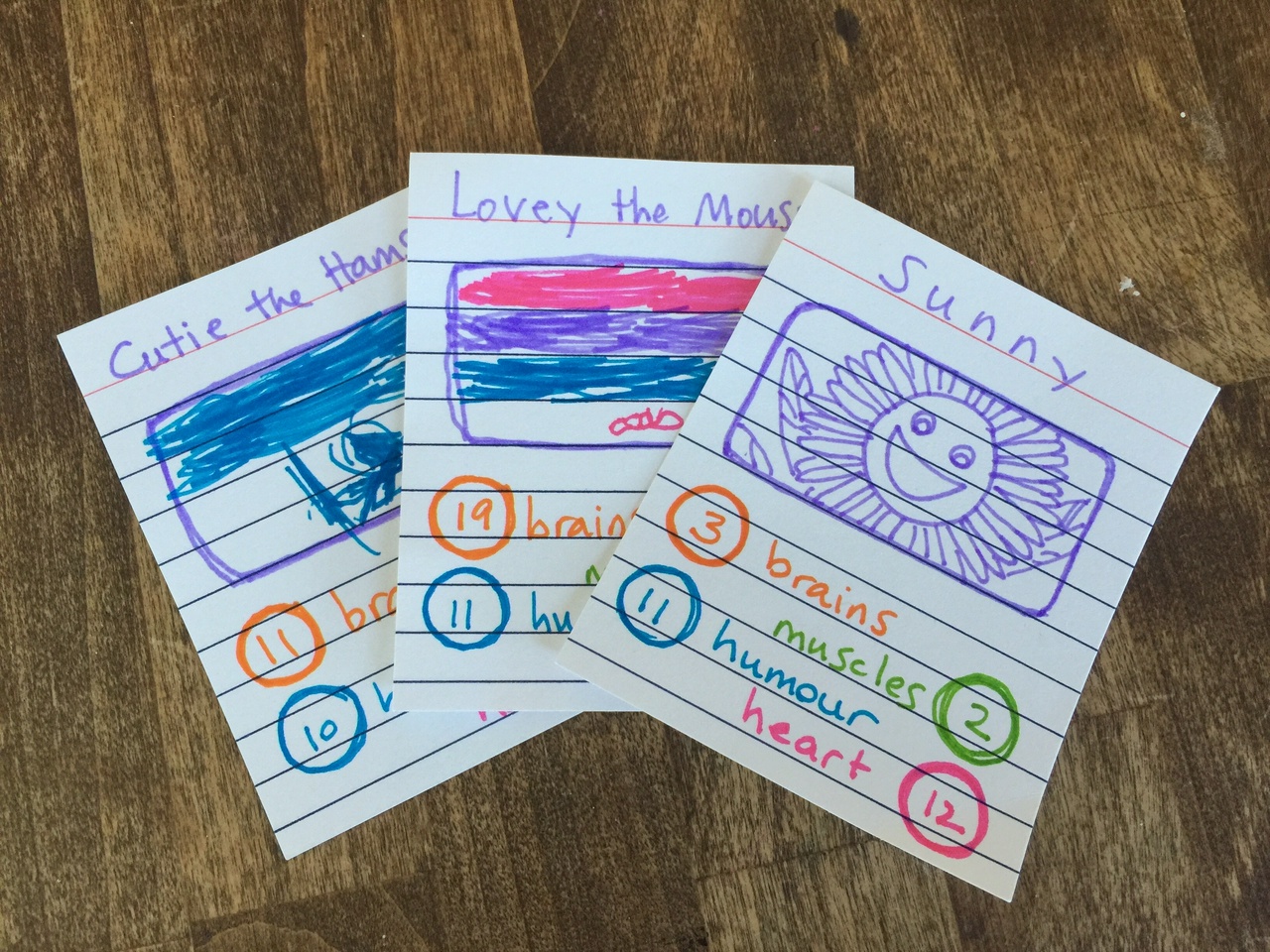

So I set out to make a deck with my own kiddos. We sat down and figured out the values we wanted to attribute, designed a template (colours work great for those kiddos who can't read yet), and set out making cards. I wanted it to be directed by W and Q as much as possible, so I set no guidelines about who the characters should be.

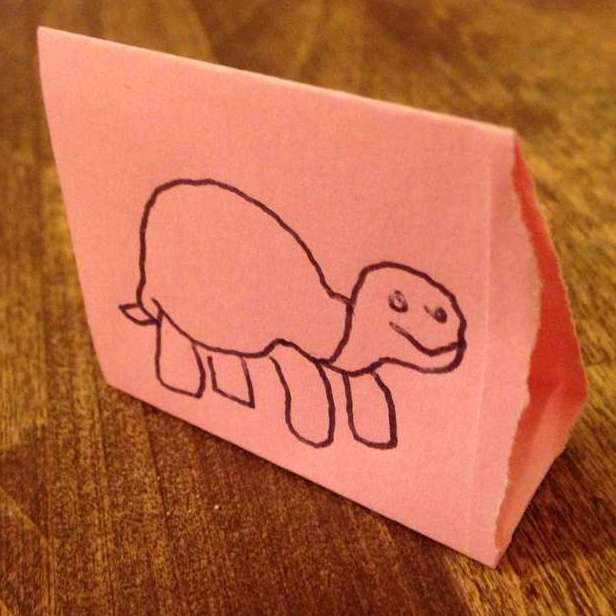

The girls decided on brains, muscles, humour, and heart. From there they drew the characters, and if needed gave them names. It was interesting to see Q start with established characters: Doc McStuffins, etc; and W went with real people: Mom, Nani. But pretty soon they both started making characters up. The next step was to get them to give each character numbers for the attributes. This was initially a challenge, as they both wanted to max out each character. We worked on comparisons — is “Dog” funnier than “Poppy the Pillbug”? This worked, but it was a bit odd with the real-person cards. With W's “Mom” card — which is clearly the “top trump” — W asked if she needed to stick to the 1-20 range for “heart”, or if she could go higher, “like a million or something”. It was very, very sweet.

W with the “Mom” top trump card