Turf!

So I’ve been working on a mobile location-based game for about 3/4 of a year now, and thought I should share more details.

When starting out on the project, I wanted to try creating multiplayer functionality. Mainly because it’s really fun playing with friends, but also because it’s a tough nut to crack. But I also didn’t want to jump into the deep end of 60fps/physics/vfx network transport – after checking out the Unity and Unreal solutions (both built-in and third party), it just seemed like too much to tackle with the limited time I had.

But I love turn-based multiplayer games (see: Pocket Tanks, I love that stuff), and it seemed like an easier place to start.

Next, I wanted to do something with mobile devices – specifically, something physical. I wanted to see if I could make a game that requires movement.

So the gameplay I ended on is this:

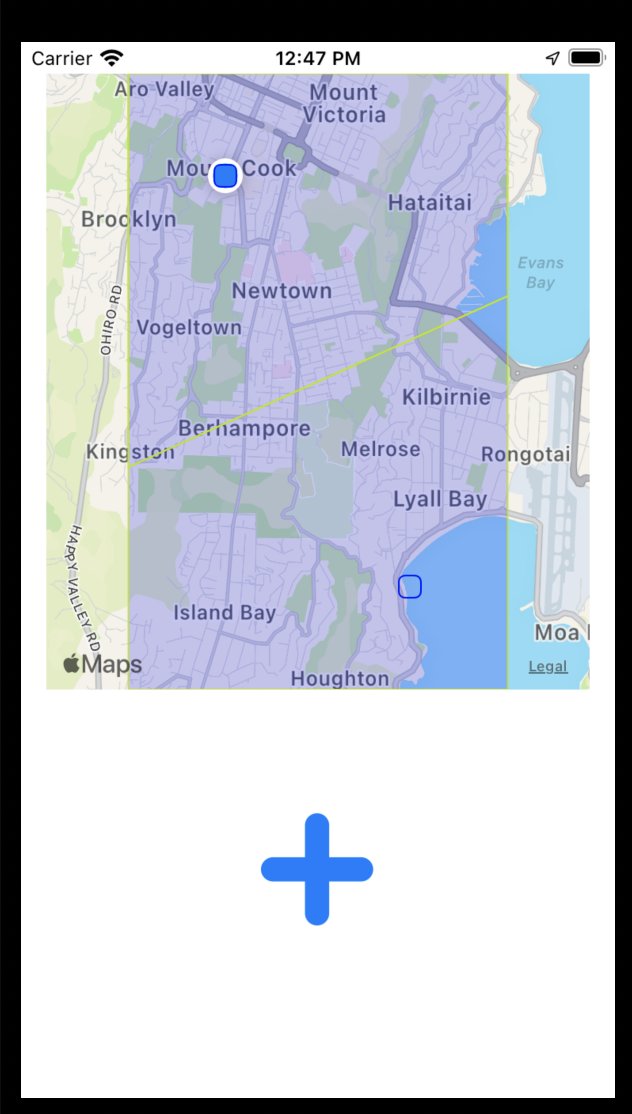

Players run around the real world, and use their devices to place virtual markers that create virtual territory. The team with the most owned territory at the end of the time limit wins.

This comes with some interesting challenges:

- Keeping track of players. Okay, so let’s learn the iOS Core Location service, and possibly the Google equivalent. I did look into MapBox, and it looks great, but I couldn’t get it to work with any tech stack (see below).

- Keeping track of state, with multiplayer replication. For this, I thought I would give Firebase Realtime Database a go. I’ve never worked with JSON-style or NoSQL databases before, so there’s a thing. But I was intrigued by the potential for pseudo-realtime networking.

- I didn’t want to force players to define territory with outlines – that seemed like too much busywork. So I went with a single marker placement at a location. That meant defining the territory programmatically. My instinct was to use Voronoi Diagramming, which I think turned out pretty well.

- Lastly, I wanted the territory to be dynamic throughout the game – so that markers would “expire”, and give up their territory. This also meant that the score couldn’t be based only upon territory, but rather a territory per timescale value (currently per second).

With all of those expectations, I researched a lot on potential frameworks to use. Cross-platform is the ultimate goal, but not the primary restriction. Although I’m very familiar with Unity, I wanted something that didn’t explicitly tie to that ecosystem — it felt unwieldy, unnecessary, and just heavy. I didn’t need all of that.

So I tried a bunch of mobile frameworks.

- Flutter. I was really hoping this one would work, and I tried it a lot. Ultimately I couldn’t get those external packages to play nicely. And the text-node-based UI design was driving me looooooooopy.

- Ionic. Yeah, I can see it for business apps. Didn’t sing to me.

- Xamarin. See Ionic, but more.

- Corona/Solar2d. I have experience in making games with Corona (now Solar2d), and really like it. But getting the hardware/database stuff working didn’t happen quickly.

- RubyMotion. In a surprise find, I tried RubyMotion — a framework that lets you use Ruby to create iOS and Android apps. I was initially sceptical, because the codebase looked “old”, and you have to pay to use it. But my fears were unfounded, as I was able to get the basic operation going very, very quickly. The Slack server is small, but quite supportive, and the main developer is constantly bringing it up to date (when not working on the also-impressive DragonRuby).

Slowly RubyMotion proved its mettle, allowing me to bring in CocoaPods for the external stuff, and visual UI with XCode (XCode isn’t even needed, which is a huge bonus — but it’s nice to use just for the UI).

After setting up the initial UI scaffold, my main goal was to get locations, markers, and voronoi working.

I had to create the Vonoroi code in Ruby, as none of the available libraries ticked every box. But that’s okay, I understand more about the sweep line algorithm now. Getting it all together was very satisfying.

Next came the real-time database. Connecting was easy — the long process was figuring out the best way to treat the data, and how to replicate it to clients. Again, I wasn’t used to NoSQL, so the idea of just duplicating data all over the place made my skin scrawl (I like normalization, okay?), but eventually I got a good schema. Client replication was hard too, mainly because Firebase docs doesn’t do a good job explaining when and why replication happens — so I’m probably totally over-forcing updates. But the data is tiny, so I’m not worried about it.

The hidden bugbear — the thing I really wasn’t expecting — was how hard matchmaking would be. It’s probably worth an entirely different post, but ultimately I wanted matchmaking to happen behind the scenes, based upon location. There were a lot of edge cases and other interesting factors. And I had to make bots, because I can’t just get humans at all hours.

In short, matchmaking was a total beast.

But I got some successful playtests, with timers, scores, and ultimately other real humans.

Right now the project is a bit stalled, as in the move to the US my priorities are elsewhere. But I also no longer have a Mac to work on. Anyone have a spare MacBook Pro they want to donate?